Slouching towards Colmar

on flat bike rides, sickly altarpieces, and stolen figs in the bas-rhin

A week in Eckbolsheim, in Z & L’s sunny little rooms atop Marianne and Makram’s house. Up early on the first morning to run into Strasbourg to collect my vélo. Cappucinos and pain au chocolats to start and then we spin along the canal towards and amongst the heims of Alsace (Achenheim, Kolbsheim, Ergersheim, etc.). We sit on the steps of Rosheim’s church for more cappuccinos and a shared éclair. Then back to the canal, through heretofore unmentioned heims like Dorlisheim and Molsheim. We tour off in Wolxheim to visit Christèle at Maison Zoeller, a medieval farmyard covered in ivy with the hum of winemaking and farm equipment nearby. At a big democratic table in their salle de dégustation, we sip minerally rieslings and decide on a bottle to bring back for our dinner with Marianne and Makram that eve.

Marianne is always there in her kitchen, or beyond in her garden. Makram is sometimes stewing aubergine or processing fruit for the next batch of jam. We stomp in the front door to find a plate of figs (stolen by Makram from a neighbour’s tree) or a freshly baked, arching Kougelhopf (that Marianne assures us is a cake, Not a gâteau, so we therefore can “eat a lot of it”) or a container of starry tomatoes with the most beautiful stretch marks (little orbs that we wish were immortalized in ceramic) on the stairs, ready for the climb upstairs. I try quetsches, a kind of Alsatian plum that crack apart perfectly like an apricot, offering up their pits to the sky and lending themselves to swift ingestion.

Elsewhere, we mount the winding steps to the top of the skeletal Strasbourg cathedral, spinning in the blender of the climb until we get up above the ancient city, to dark storm clouds on the horizon. In the museum opposite, we think that a man is moving furniture about upstairs in the medieval gabled building, until a crack of lightening lights up the gallery (first mistaken for the boldness of all the museumsgoers simultaneously taking a flash photograph) and a rumble again — an absolute tumult of a storm and the realization that the big man upstairs is rearranging furniture in the grandest sense.

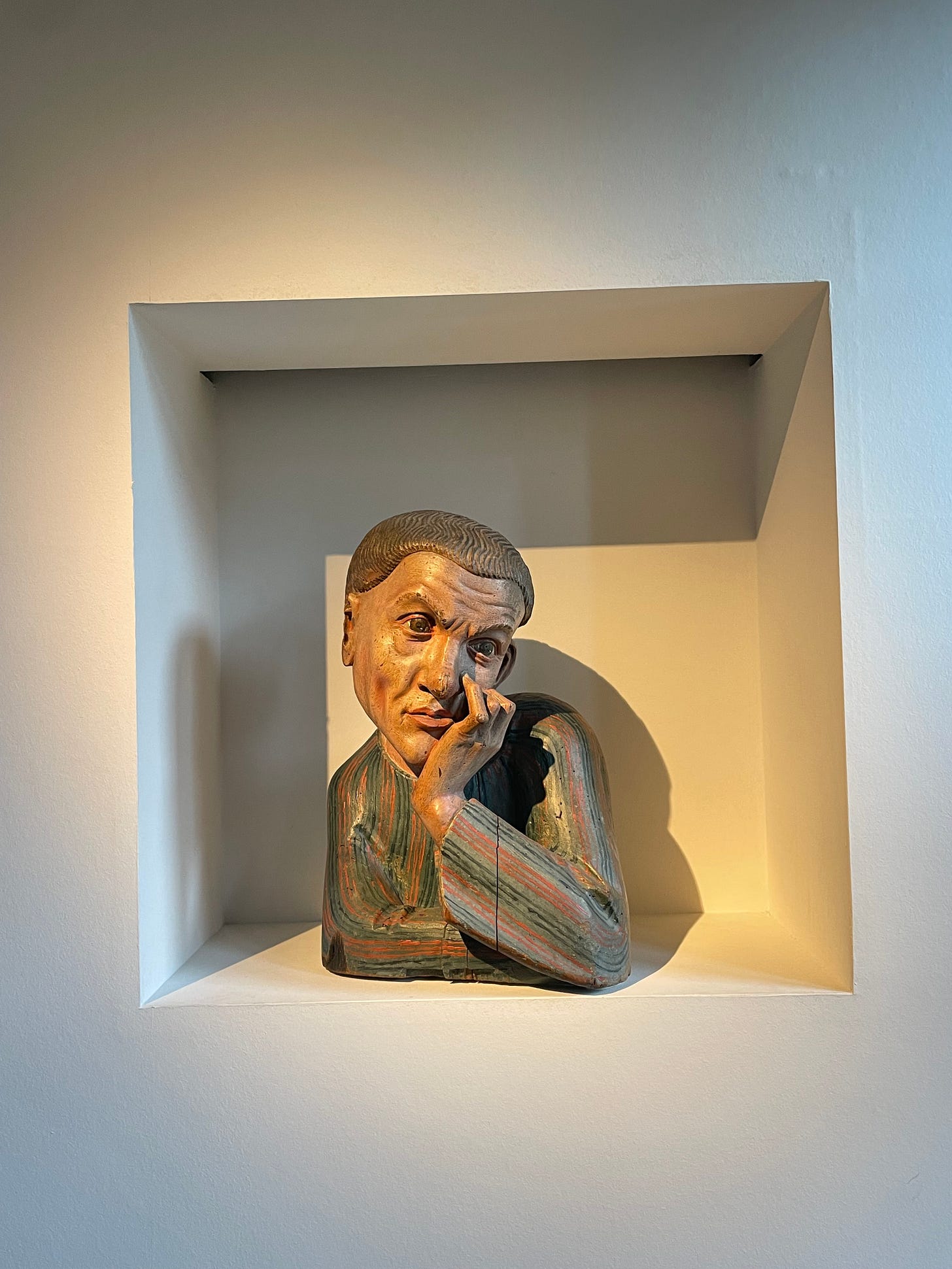

Outside the rain falls, inside, I lean in on a wooden bust, Buste d’homme accoudé, tucked away in a niche on one wall. He rests his chin on a propped hand, brow furrowed in interest or emptiness, striped shirt one I’d like to wear myself. Opposite, Conrad Witz’s St Mary Magdalene and St Catherine hangs in crisp, generous, sumptuous clarity.

Somewhile later, we pile into a rental car with a huge screen that doesn’t work because we didn’t buy that package and roll towards Colmar, sandwiches packed in our totes (chorizo, comté, quickled shallot on slices of a crumbly dense loaf and a dessert pb & j). The Musée Unterlinden is a revelation. A 13th-century Dominican sisters’ convent houses the museum (it was also, importantly, a public baths building in the early 20th-century).

Along the nave, these galactic, kitsch, sublime, grotesque scenes stand grandly and are let to breathe. The Isenheim Altarpiece was painted across four years, from 1512 to 1516, by German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald. Originally, Grünewald painted the panels for an Antonite monastery at Isenheim, near Colmar. They were installed on a tremendous wooden structure with a series of hinged panels that would be folded out to reveal different scenes and tell different stories. This first architecture of the piece had two sets of wings that could display three configurations. I imagine them as older, more original (and sickly) examples of the paneled books from childhood where you could change the beginning, middle, or end of the story by flipping and unfolding. During the French Revolution, the altarpiece was disassembled and has never been put back together again, now standing together as parts of a whole.

The order at Isenheim was dedicated to care of the sick, particularly for those suffering from “St Anthony’s fire” (what we would call ergotism). Grünewald’s figures are sometimes fantastical but the dismal symptoms that plague them are not fantasy. The altarpiece was a source of devotion and comfort in its showings of death without disguise. Grünewald offers, perhaps paradoxically to us modern interlocutors, both salvation and relief. They are grand recognitions of agony.

Before us, W.G. Sebald slouched toward Colmar and wrote about it in The Emigrants:

“About ten or eleven in the evening I arrived in Colmar, […] the next morning, without delay, went to the museum to look at the Grünewald paintings. The extreme vision of that strange man, which was lodged in every detail, distorted every limb, and infected the colours like an illness, was one I had always felt in tune with, and now I found my feeling confirmed by the direct encounter. The monstrosity of that suffering, which, emanating from the figures depicted, spread to cover the whole of Nature, only to flood back from the lifeless landscape to the humans marked by death, rose and ebbed within me like a tide. Looking at those gashed bodies, and at the witnesses of the execution, doubled up by grief like snapped reeds, I gradually understood that, beyond a certain point, pain blots out the one thing that is essential to its being experienced - consciousness — and so perhaps extinguishes itself; we know very little about this.”